Violeta Arnaiz is the director of the TMT (Media and Telecommunications Technology), Intellectual Property and Software Area at PONS IP, a consultant firm that is an expert in the management, protection and defense of organizations’ intangible assets.

Some time ago, while we were having a coffee, we began to talk about the architectural visualization industry, how relatively new it is, how little known in general, its importance within the construction economy and above all, the legal framework of the same. That’s why we decided to get out of our usual line of content and make that conversation an interview. We hope you find it useful.

1. Who is Violeta Arnaiz? Tell us briefly about your career as a lawyer.

Since I finished my law degree in 2007, it was clear to me that I wanted to direct my professional career towards intellectual property (at that time still a great unknown to most). I specialized in this subject through a master’s degree (in intellectual and industrial property and new technologies) that I studied at the Autonomous University of Madrid. Since then I have been professionally dedicated to this discipline, which, moreover, has not stopped growing for a second and facing constant challenges derived from technological advances.

2. What is intellectual property? What types of works does it protect?

Intellectual property is the branch of law that is responsible for protecting original artistic, literary and scientific creations. Within this protection umbrella are creations such as visual creations (plastic arts, photography, drawings) made by any means, even when the author uses analog or digital tools, as would be the case with architectural visualizers, audiovisuals (films, series, video clips), musical compositions, literary works, architecture, sculpture, choreographic works, software, databases or video games.

And how do you protect them? Well, said in a very simple way, allowing their authors to control the use that can be made of their creations. In this way, the authors of, for example, a musical work, may use it exclusively in the market, prohibiting others from doing so, or authorize third parties to exploit it in exchange for a price (or not) that may consist of a fixed amount. , or a percentage of the income generated by the work. In addition to this, intellectual property legislation gives the author, among others, the inalienable right to be mentioned as the author of that work.

3. Is there any distinction in terms of Intellectual Property, when the creation is born as a order made by a third party or when it is carried out within the framework of your employment relationship?

Yes. The IPL establishes that, unless otherwise agreed in the employment contract, when as a consequence of the position you hold in your company you must create protectable works, the rights over these will belong to your company. However, in the event that, for example, you work as a freelancer and you are commissioned, the rights will remain in your possession unless you expressly assign them to the person who entrusted you with the work.

4. Specifically in the Architectural Visualization industry, where we create images from the creation of others (architects, interior designers, etc.), is there any legal regulation?

This is precisely the point that presents the greatest challenge when analyzing the form of protection of ArchViz works. When starting from a previous creative work, the first thing we need is that the architects / interior designers who have made that first creation, on which we are going to work, give us permission to use it. When a job is commissioned, this usually «goes on its own», because all these plans / images are sent to him, and it is known that they are necessary materials for the visualizer to be able to carry out his work. But the theory is that you need that prior authorization.

Once obtained, for the result of our work as viewers to be also protectable, a second requirement must be met: that our work be original (that is, that it has sufficient originality with respect to the starting point, which are the plans or images that are receive from architects or interior designers). This is the most subjective part and the most difficult to assess, but I am certainly inclined to think that, to the extent that the visualizer makes creative decisions that affect the final result of the work (with the same starting plans for sure as the final work of one viewer and another will not be the same), this originality will exist, and the final work (which in legal jargon will be called a «derivative» work, as opposed to the «original work» from which it starts) will be protectable by intellectual property law. And its rights will belong to whoever created it, that is, the viewer, not the architect or interior designer.

There are other issues that can complicate the puzzle a little more, such as the use by viewers, when working, of other foreign protectable elements. I am thinking of pieces of designer furniture, sculptures, paintings, illustrations, photographs, etc. that are rendered and inserted into the images. In this case, if these elements are original and protectable (and not in the public domain -it is clear that we can already use any painting by Goya or Velázquez-) in theory we should have a permit or license for their inclusion in our work.

Or even in resources (textures, HDRi…) from repositories created by other professionals that may be original. In the latter case, the use of these elements is usually conditioned to the acceptance of the terms and conditions of a license that is accepted when «purchasing» the resources. And it will be there where what happens with these elements will be regulated, and under what conditions the viewer is allowed to use them.

The use of these external elements does not prevent our work, if it is original, from being protected. But it will have some consequences, such as: (i) the need to obtain the appropriate permits or licenses for the use of these elements, as we have anticipated, and (ii) the impossibility of claiming those elements as our own in our creation (to explain it in In colloquial terms, what we would have intellectual property rights over would be “everything else”).

5. In general terms, what terms should a contract include in order to correctly cover the rights of creators? What advice could you give to companies and people who work as freelancers, when establishing a business relationship with a potential client?

The first thing that must be taken into account is that by ordering an ArchViz project (for example) and paying for said work, the viewer does not automatically assign the intellectual property rights that correspond to him on his work. If a client orders an ArchViz work and, once created, wants to be able to exploit it in the way he wants, he must incorporate this assignment in a contract where, expressly, the viewer grants him the intellectual property rights over that work.

The usual thing, as I have seen in some of the contracts that are signed in the ArchViz sector to which I have had access, is that the client who commissions the work does not ask the viewer for all the rights to the work, but only the granting of a license to make a specific and limited use of the material (for example, include it in the tender or in the specific project). If you usually sign this type of contract, I give you three tips:

1. The extent of that use that you allow them to make (the license that you grant them) may vary depending on what the client needs. Read that part of the contract well, and if you have doubts or think that what they ask of you is excessive, ask and open a debate about it. In the end, it is about making both parties comfortable in the contracts, although always, to reach agreements, you have to give in a little.

2. Do not forget that whenever that client uses the work, they must give you credit as authors (the paternity right cannot be assigned). The way to mention you as authors of the work will depend on the type of exploitation that is carried out.

3. And, of course, that if the license that you have given to the work has not been configured as «exclusive», you can continue to use the work in the way you want (because your intellectual property rights will continue to belong to you, even if you have authorized a client to make certain uses of it).

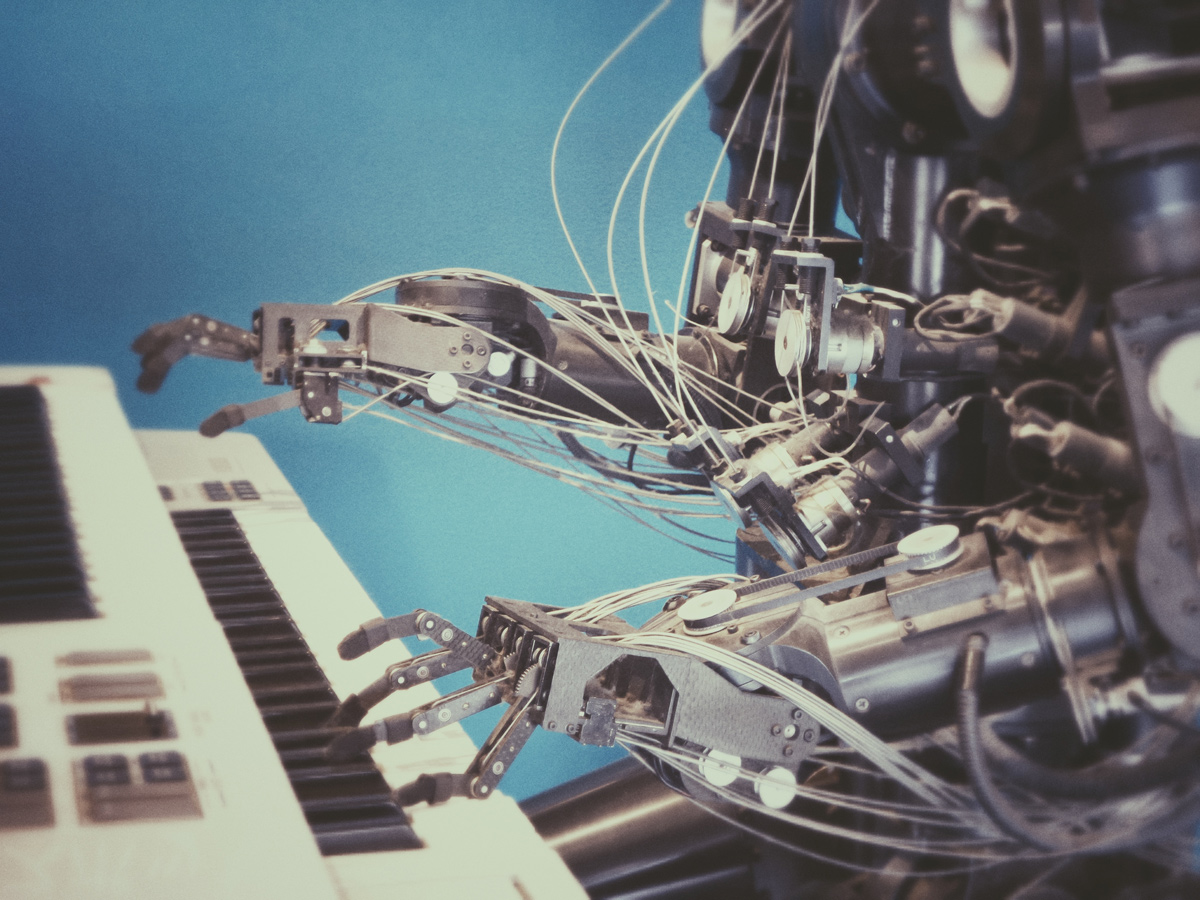

6. What do you consider to be the challenges facing our industry in legal matters? How do you see legal development in creative fields with the emergence of new technologies? Specifically, talk to us about artificial intelligence and how it affects intellectual property and, in particular, the creation of images through these techniques.

Every day, technological advances lead us to completely new realities that require specific legal responses. Artificial intelligence (AI), which has been on everyone’s lips in recent months, is a good example of this.

Regarding intellectual property, the emergence of AI poses two major challenges for us. The first of these is to determine whether works created by AIs have any type of legal protection and, if so, who would be the owner of those rights. At the moment, the answer to this question, in those jurisdictions where it has been raised, is negative. In the United States, there are already several resolutions denying protection to works created exclusively by AIs, based on the fact that there has been no human intervention in their creation. And this requirement (human creation) is essential for intellectual property rights to arise. In Europe, although the courts have not yet pronounced on this issue, the law is very clear in conditioning protection to human authorship, so a work created exclusively by an AI would be outside the protection of intellectual property and could be used freely by anyone. I add the word «exclusively» because what can happen is that a person, assisted or aided by an AI, creates works, and in that case, these would be protectable (just like if a visualizer creates works helped by specific software, or a photographer with a camera).

This issue is related to another: does the user of an AI (for example, and in terms of images, Midjourney or Dall-E) who enters certain parameters for generating an image have any intellectual property rights over the generated images? In principle, if human intervention is minimal, what we have just seen would apply (without human intervention in the creation of the image, there are no intellectual property rights, so the work could not have protection or generate any rights, neither for the AI nor for the user of the tool). If we understand that human intervention is relevant to the creation of the work, this conclusion could be questioned and it could be argued that there is a right for the user who has contributed to its creation. But even in this case, we would have to resort to the Legal Terms of the specific platform used, which may impose restrictions on your ownership of that image – in fact, they do, as you can see, for example, here.

The second question raised by the emergence of AI is: what happens to all the protectable works (software, images, texts, renders, photographs, etc.) that are used to train these AIs? Can they be used without permission? Let us remember that AIs, to create images, texts, code, etc., are precisely fed by third-party images, texts, and code, which may be protected. And not only do they use them for their training, but in the results they offer to their users, parts of those previous works may be reproduced.

Recently, the first lawsuit has been filed in the USA over the use that Copilot, a product of a company partly owned by Microsoft, makes of third-party source code to train an algorithm capable of creating code autonomously. Also recently, the music industry has taken a step forward in this regard, announcing that it will introduce contractual prohibitions to prevent the works and performances of its artists from being used to train AIs.

Another important challenge is derived from the development of the metaverse and how to transfer our «national» or «regional» legal frameworks to this new borderless virtual world. Regarding specifically to visualizers, what role will they play in recreating spaces in this new virtual world? Will you be prepared as a collective to defend your copyrights and manage them in the best possible way when the clients are the large multinational companies that are «building» the main metaverses?

Although I believe that your main challenge is still being aware that your work, if it is original, is protectable by copyright, just like a song, a movie, or software. And that these rights are an asset that constitutes the basis of your business, and as such, you have to learn to recognize and take care of them.

We hope you found this interview interesting. If you want to know more about Violeta’s work and the services that PONS IP offers, you can visit the Website

As always, we invite you to leave any comments or suggestions at the bottom of this page.